Part 6 – Records (part 1)

Records!

So we eventually come to records, the final links in getting our turntables to perform their magic and keep us spellbound with the wealth of information contained within them. Although we all know what they are and what they look like, the following summary might be useful:

What is a record?

A gramophone record, commonly known as a phonograph record (in American English), vinyl record (when made of polyvinyl chloride), or simply record, is an analog sound storage medium consisting of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The groove usually starts near the periphery and ends near the center of the disc. Phonograph records are generally described by their size (“12-inch”, “10-inch”, “7-inch”, etc.), the rotational speed at which they are played (“33 r.p.m.”, “45”, “78”, etc.), their time capacity (“Long Playing”), their reproductive accuracy, or “fidelity”, or the number of channels of audio provided (“Mono”, “Stereo”, “Quadraphonic”, etc.). Gramophone records were the primary medium used for commercial music reproduction for most of the 20th century, replacing the phonograph cylinder, with which they had co-existed, by the 1920s. By the late 1980s, digital media had gained a larger market share, and the vinyl record left the mainstream in 1991. However, they continue to be manufactured and sold in the 21st century. The vinyl record regained popularity by 2008, with nearly 2.9 million units shipped that year, the most in any year since 1998. They are used predominantly by young adults, as well as DJs and audiophiles for many types of music. As of 2010, vinyl records continue to be used for distribution of independent and alternative music artists. More mainstream pop releases tend to be mostly sold in compact disc or other digital formats, but have still been released in vinyl in certain instances. The following image shows the relative size of a 12” LP record to a 7” single and a CD disc.

How is a record made?

The first step in making a record is to make a recording of the artist or the group. This can be done by various means, e.g. cassette reel or digital storage media. The resultant recording is then used to drive a cutter head of a cutting lathe. The cutter head is fitted with a cutting stylus which usually has a sapphire as opposed to a diamond as it resists wear better than a diamond. Diamond is a good material for playback of vinyl, but the sapphire will outlast a diamond and produce superior recordings. The cutter head can be seen as a stylus working in reverse. It literally cuts grooves into blank discs, usually called acetates. Acetate is actually not the correct term as the soft material disc is actually lacquer coated with cellulose nitrate, but professionals still commonly refer to them as acetates. Once the cutting stylus is working it cnnot be stopped without ruining the disc. Careful calibration and setup is performed before this important process is started. A 14” disc is usually used for a 12” disc end result. A silent groove test cut is made, outside the diameter of the disc. This is used to test that the groove size is correct and that the noise level is low. Once the cutting stylus is started a lead-in groove is cut with wide spacing, followed by the information section with equal spacing, and groove depth and width also physically at different points from start to finish. At the end of the sound recording a spiral lead-out groove is cut by speeding up the lead screw of the cutting lathe, either manually or automatically, followed by a lock groove. Shown here is the Neumann VMS70 Cutting lathe, and also another cutting lathe with an Ortofon cutting stylus.

The next step is to deposit a fine layer of silver nitrate on the surface of the lacquered surface. This is done by sensitizing the lacquer surface by dipping it into a stannous chloride which is then washed off in a water spray, leaving a very thin coating. Silver nitrate is then sprayed onto the disc and the black becomes a mirror finish of silver in a matter of seconds. The stannous chloride acts as a catalyst to promote the process. The silvered disc is washed and moves on to the next treatment. The next objective is to build up a solid metal backing onto the silver coating. This negative mould is then completed after the lacquer is stripped away, leaving the inverse of the original record and its grooves. A fine grained layer of copper coating is added without disturbing the fine groove modulations. The back of the newly formed “record” is then made stronger by piling multiple layers of metal over each other. Once the lacquer is removed by the blow of a hammer, this is called the matrix. The matrix is the first and only existing copy of the original lacquer disc and in most cases is used to produce a “mother”. This mother is then subjected to another plating process ending in another metal negative which is the desired “stamper”.

Since the mother is made of metal it can be re-plated many times over, producing negative after negative in metal, all identical to the first. These negative offspring masters can now be used to press thousands and thousands of records. The next step is the insertion of the two sides of the record into a press with heated sides. The two negative halves of the record then clampdown together to form a record after the necessary vinyl pellets are inserted into the cavity created by the press closing. Heat comes from super-heated steam at 300 degrees and then cooled down with cold water. Record and label are bonded together in the pressing. As the pellets melt and conform to the shape of the stamper, they immediately cool down and harden when the water replaces the heat. After coming out of the press the newly made record has its ragged edge trimmed and cut neatly by a circular cutting device and then passed on for inspection. Records are rejected by visual inspection and playing checks. All rejected discs are thrown in large bins and recycled. Finally the record is placed into its inner sleeve and outer jacket sleeve and then distributed out to dealers and retail outlets.

What do record grooves look like?

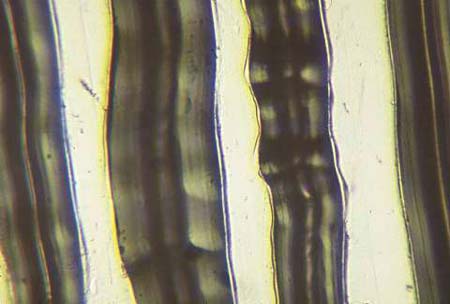

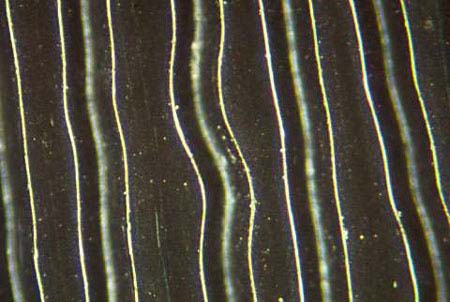

The record grooves can only be seen properly once magnified significantly, due to their tiny size. Grooves are typically measured in micron (millionths of an inch). It is easy to imagine music being lost if the stylus and arm is not of high quality, or if there is excessive free play in the bearings. The process of the stylus following the groove and staying in contact with groove wall surface becomes difficult, if not plain impossible. Records will either contain mono sound or stereo sound. With mono sound the grooves will be modulated only horizontally (from side to side with even depth throughout), but with stereo sound the grooves will be modulated horizontally as well as vertically (the depth will differ continuously). Please have a look at the accompanying images. The first is a mono groove magnified 300 times, the second a stereo groove magnified 400 times.

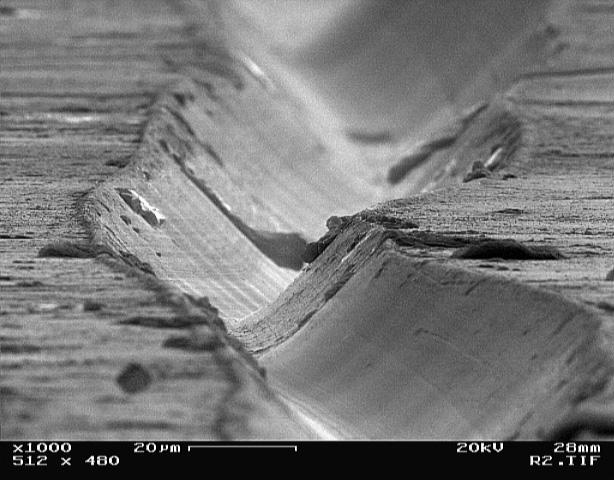

It is really difficult to imagine what a stylus needs to do if one does not see a proper image that shows the complexity of what the groove wall really presents under normal practical operation. The following image shows a relatively easy modulated passage that needs to be tracked by the stylus. Under most conditions the groove wall is far more complex than this, when sound becomes more complex and more instruments are playing together. To truly understand the complexity of the stylus and what it needs to be able to extract from the groove, please have a look at the second image.

How should I look after my records?

Records are much more durable than most people give them credit for, but they should still be treated with respect and in a proper manner. The simplest and best advice as regards records is to store them in an upright position, within their inner sleeves and inside their outer covers. This offers the best protection and will also prevent basic warping. There are various storage solutions available that will create decent and dependable storage. For obvious reasons one should not expose records to extreme temperatures as the records will deform and warp. From well-designed and basic structures to very advanced and elaborate cabinets and wall units the most important consideration is the fact that the records should be stored upright. Wouldn’t a collection like this be lovely?

Other factors that would affect records and their performance is extreme humidity, although not directly problematic to the records themselves, the covers can start changing shape if they absorb too much moisture and then dry out at a later stage. So avoid extreme temperature changes as well. An even temperature and dry conditions are good. Records should always be placed back into their protective sleeves after playing and keep dust off of them. Basic hair and fluff will usually be scraped out of the way by the stylus’ general operation, but remove any such items anyway if you have the opportunity.

Cleaning records can really only be done properly by using a professional record cleaning machine. Machines like Okki Nokki are simple to use and very effective at what they do. Even though they are not cheap they are an absolutely indispensable piece of equipment and will certainly repay their expenditure many times over. In many cases where vinyl users buy a lot of good quality secondhand vinyl, they are absolutely crucial in their preparation and preservation of the vinyl format. Many records that are initially thought to be noisy and damaged very often sound superb after treatment. Even though they cannot repair damaged records, they are instrumental in removing all debris and rubbish from the grooves and at least make certain that no further damage can occur, or the existing dirt in the groove can be pressed into the vinyl compound where it will cause much worse damage. Record cleaning machines usually clamp the record down on a flat surface. The record is then scrubbed with a wet solution and a bristle brush and while the debris and dirt is in suspension in the fluid, the suction arm sucks it up and deposits it into a separate container. Here it will either dry out or it can be removed and disposed of. Shown here is the Okki Nokki Cadence. Many other manufacturers also produce units and budget should be considered, as some can really reach high prices, depending on their functionality.

If using a record cleaner, the fluid usually consists of a formulation of isopropyl alcohol and distilled water. The isopropyl alcohol is stable with the vinyl compound and will clean all but the most stubborn of gunk from the record surface. Some manufacturers believe that no form of alcohol should be used, and subsequently manufacture alcohol-free solutions. Once cleaned the records should be placed in decent inner sleeves.

There are a variety of suppliers that manufacture inner sleeves of different materials and thicknesses. Generally these sleeves have anti-static properties and will not scratch the surface of the record as they are slid in or out. Companies like Discwasher and Mobile Fidelity also supply very high quality sleeves. Even though they are a little bit pricey one should ask what price one places on a damaged record.

In the next installment we will continue our current thread of discussion on records and related issues.

Recent Comments